PORT TOWNSEND — The Port Townsend Film Festival programmed films discussing themes of housing ranging from the unhoused to the inequitable dynamics present in employee housing to explorations of architectural trailblazers in kinetic architecture.

In addition to the films, the festival hosted a community housing discussion.

The housing discussion, moderated by Port Townsend Film Festival’s Marketing and Development Director Keith Hitchcock, included a panel with “Michael and Damian” director Gabe Van Lelyveld and Michael McCutcheon.

The conversation, which immediately followed the screening of “Michael and Damian,” mostly centered around questions and comments about the challenges facing unsheltered people, but it was framed as an informal opportunity for attendees to enter into a conversation about what was on their mind with regard to housing.

Among the attendees was Viola Ware, Olympic Community Action Programs’ director of housing and community development.

For some people, living in a shelter among other unhoused people is very challenging, Ware said.

“I can’t live in an apartment with another adult,” she said.

Working with veterans helped Ware to reconsider what housing looks like.

“I work with vets who lived out of a Jeep in the desert in Afghanistan, and they had a home, but they didn’t feel safe in their home,” Ware said. “What they felt safe in was their car. Because no matter what happens, you can take your car somewhere else.”

“Home From Work” is a short documentary which focuses on the pitfalls of employee housing on Orcas Island.

“A lot of friends live and lived in employee housing,” co-director Alex Fleming-McNeil said. “I heard a couple stories of folks who were evicted on really short notice from employee housing when the season turned. That was what got me interested in the topic.”

The film presents employee housing as providing inhabitants with no protections.

“In almost all housing situations, even if you don’t have a lease, you have this basic standard of tenant protections through state and federal law,” Fleming-McNeil said. “In this case, because housing is provided through the employment contract, it’s kind of a gray area in the law.”

The island cannot accommodate any more people than those already there, said a restaurant owner named Drew in the film’s opening statement.

“Affordable housing doesn’t exist on this island, unless you’re in employee housing,” said Patricia, a woman in the film.

Patricia is a bartender who was evicted along with her co-workers when her employer Rosario Resort was sold.

Patricia’s rent increased from $300 per month to $1,200 monthly, a third to half of her income.

Sexual assault has been prevalent in every workplace she’s been in, Patricia said. Over and over again, she’s seen men given slaps on the wrist before returning to employee housing, she added.

Pluto, another subject of the film, described living in employee housing.

“I currently live in a room in one of the parts of the hotel that I work for,” Pluto said. “This is the first room that I’ve ever lived in that truly felt like mine. I feel like I belong in this room, and this is my space that I come back to and relax.”

Pluto described the living situation as carrying with it a level of volatility.

“I try not to think about if I didn’t have this job, because it sounds so catastrophic,” Pluto said. “It sounds like I’m catastrophizing, ‘Oh, if I lose my job, I lose everything.’”

The catastrophe is a reality, Pluto said.

Fleming-McNeil said it was a joke that employers would ask prospective employees if they had housing. If they said yes, they were hired.

It’s not just employees who are having to deal with this,” Fleming-McNeil said. “It’s not employers who are always cackling, gleeful that they’re putting people in this situation. There’s a bigger housing crisis and shortage that both sides of the equation are responding to.”

The film is presented in a whimsical style. Fleming-McNeil said the intent was to represent the beauty and attraction of the island, then to contrast it with the more neutral realities of people’s living spaces and situations.

Beyond the examples of employee housing present in the film, Fleming-McNeil said he knew many others on the island which he called sub-par. Some yurts or trailers lacked sufficient heat and pipes often burst in the winter, he said.

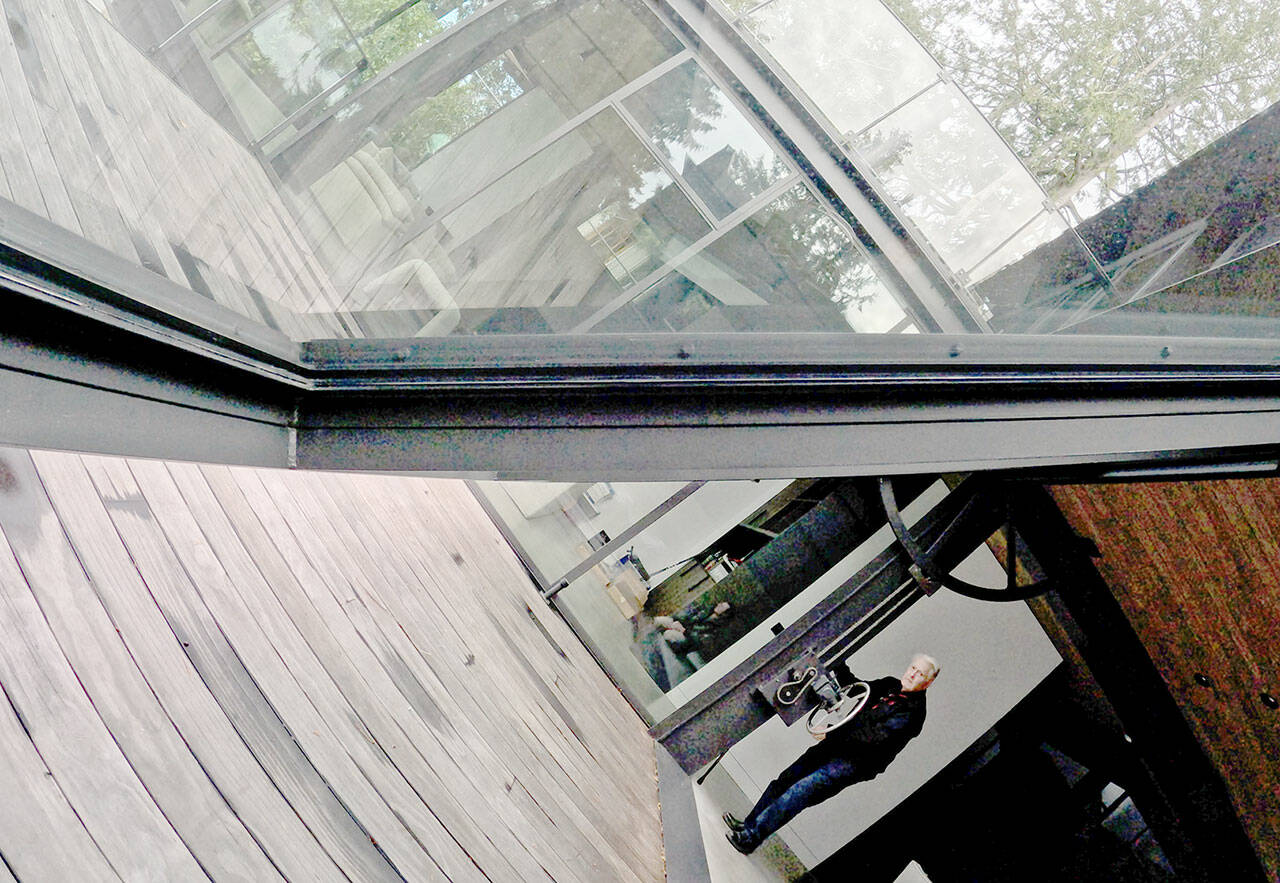

The festival also featured short-doc “Counterweight,” which illustrates architectural work that accomplishes the outer limits of how engineering can dissolve the lines between the inside and the outside world.

The expertly shot film explores the fascinating work of Seattle architecture firm Olson Kundig, known for its innovation in kinetic architecture, or houses that move.

Early in the film, a young girl is seen cranking a wheel which lifts a wall of a home.

“They have created magic that exists within our physical reality,” said Christian Sorensen Hansen, who co-directed the film with Austin Wilson. “It’s so cool. When you spin that wheel and this 30,000-pound door lifts effortlessly into the air, it really feels like magic.”

In other shots, the roof of a building is cranked completely open. In yet another, an entire house moves easily along a stretch of train track.

“You can grab a handle, push a button, pull a lever, crank a wheel and make such amazing difference in your material state,” said Steven Rainville, principal and owner, in the film.

“When you move that gizmo, you’re basically the motor of this large device,” said Tom Kundig, principal, owner and founder, in the film. “All of the sudden, the human body becomes part the engineering of this thing.”

The firm’s resident gizmologist, Phil Turner, who is featured heavily, said he enjoys the work so much because he sees it all as problem solving.

At one point, Turner worked as a logger.

“I’ve always been really good at figuring out how to move really, really heavy things manually,” Turner said in the film. “I like to work puzzles. I guess everything’s a puzzle.”

Sorensen Hansen, a huge fan of architecture and the work at Olson Kundig, said the housing crisis is close to his heart and that he has often considered how accessible kinetic architecture can become.

“Kinetics don’t have to be a luxury item,” he said. “It doesn’t have to be something that only exists in really expensive homes. We already see kinetics in every building: doors, operable windows and garage doors. But we can dream bigger and execute on a larger scale without a huge price tag.”

________

Reporter Elijah Sussman can be reached by email at elijah.sussman@peninsuladailynews.com.