THE BIBLE POINTS out one of mankind’s failings. “You lust and do not have; so you commit murder.” (James 4:2) All too often we see this theme in the news.

It was exactly 88 years ago today (Oct. 4, 1937) when tragedy struck in the small community of Mora.

Mora is on the north side of the Quillayute River near La Push.

The first reports told how Linwood Sproul, 58, was accidently shot and killed by a close friend and neighbor, Ralph Carson.

On Oct. 4, Carson borrowed a 22-caliber rifle from Sproul to shoot hair seal in the Quillayute River. Sproul lived by the Dickey River. The account of events starts about 7:30 p.m. when Carson returned the rifle to Sproul’s home.

Carson and Sproul were sitting in the living room. Sproul was reading the newspaper, while Carson had the gun on his lap to start cleaning it.

The gun discharged and Sproul was struck in the upper abdomen. He died almost immediately.

In an adjoining room was Sproul’s daughter, Rozella Andrews, and his 16-year-old granddaughter, Alma Andrews. Neither of them saw the rifle discharge. Alma immediately called Deputy Sheriff W. E. Holenstein.

Linwood Cornelius Sproul was born on July 14, 1879, in Bristol, Maine. Sproul was an old-timer in the West End of the county and was the driver of the Mora school bus. Sproul gave Carson various handyman jobs.

An inquest was held and the coroner’s jury determined Sproul’s death was an accident.

Deputy Holenstein and Sproul’s friends had their suspicions aroused, though. Friends of Sproul were not convinced it was an accident. Deputy Holenstein noted that Carson contradicted himself whether the rifle was loaded or not. The day of the murder was the first time Carson had borrowed the rifle. Carson “forgot” the dirty rifle and waited until after dark to return and clean it.

Carson also had served in the army and knew better than to clean a gun in the house, pointed at someone.

It also was evident that Carson was attracted to Sproul’s granddaughter, Alma Andrews.

Deputy Holenstein also thought Carson was “shifty-eyed under questioning.”

Neighbors and friends of Sproul kept in close touch with Deputy Holenstein, reporting anything questionable that was happening.

Carson’s attraction to Alma grew, but things went too far in August 1938. This sort of event is not something a young girl wants to talk about openly.

The first break in the case came from Mrs. Wilma Smith. Smith stayed in a local hotel with Alma for a time. Alma eventually opened up about the rape. It was enough for Prosecutor Ralph Smythe to hold Carson on a morals charge.

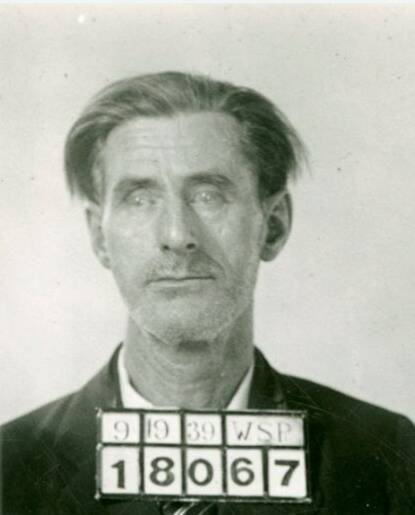

On March 21, 1939, Carson pleaded guilty to carnal knowledge of female child. Carson was sentenced to 20 years in prison. While Carson was jailed, Deputy Holenstein continued to question Carson about the fatal shooting of Sproul.

Carson continued to maintain the shooting was an accident. Holenstein asked, “You insist that you have been telling us the absolute truth!” Carson answered, “Yes.”

Holenstein countered, “Then you would have nothing to fear from a lie detector. Would you submit to it!”

Carson wavered, stating he wanted to consult his attorney. That became the big break in the case. Carson realized he had shown his hand by fearing the lie detector. That was enough to break Carson.

On March 25, 1939, Carson pleaded guilty to first-degree murder. His motive? Carson’s love for Sproul’s 16-year-old granddaughter. “I do not know why I did it, except the Lin (Linwood Sproul) might come between me and his granddaughter, Alna, whom I love.”

Carson recounted the actual events to Prosecutor Ralph Smythe. He came to Sproul’s home on the pretense that the rifle needed to be cleaned. He retrieved the rifle and cleaning supplies and went to the sunroom where Sproul was sitting in a deck chair. Sproul had a newspaper in front of his face.

Carson placed the rifle across his knees as if to clean it. He raised the muzzle slightly, pointed it at Sproul, and pulled the trigger.

Sproul lunged forward. Sproul’s last words were “You should not bring a gun in the house loaded, you know better than that.” Carson did know better. Sproul did not realize he was shot intentionally.

Carson’s trial began on Wednesday, April 19, 1939. During the second day of trial, Carson became hysterical. The court recessed for the remainder of the day. Two doctors examined Carson and concluded the hysteria was a sham.

On the third day of trial, April 21, 1939, Carson declared his confessions were given to protect the women involved. He claimed the sheriff was going to arrest Sproul’s daughter and granddaughter if he did not confess. That claim was baseless.

By the end of the day, the jury convicted Carson of first-degree murder.

It was later discovered that Carson had concealed a pocket mirror in his clothing. While in jail, he broke it in two and tried to slash himself.

On May 3, 1939, Judge Ralston sentenced Carson to death by hanging. Carson was the first person to be sentenced to death from Clallam County.

On May 11, 1939, Carson was booked into the state penitentiary at Walla Walla.

Carson was scheduled to walk the “last mile” on Dec. 8, 1939. When the time came, Carson showed no nervousness when he walked to the gallows.

It was reported that Carson found God while he was in prison. In his written statement, he wrote, “I depart from this world with peace in my soul to meet my Creator through my Lord and Savior.”

Fifteen minutes before his execution, Acting Governor Victor A. Meyers called the prison to be sure everything was ready. There would be no commutation of Carson’s sentence. Meyers found no reason why the penalty imposed by the court should not be carried out.

At 12:07 a.m., the trap door was released. At 12:19 a.m., prison physicians declared Carson dead. Carson was 54 years old. Carson’s body was interred in the prison cemetery.

The Bible describes lust as a “fire that consumes” (Job 31:12). Ralph Carson found out that his lust was not worth the consequences.

________

John McNutt is a descendant of Clallam County pioneers and treasurer of the North Olympic History Center Board of Directors. He can be reached at woodrowsilly@gmail.com.

John’s Clallam history column appears the first Saturday of every month.